In late summer of 2022, myself and my wonderful frolleague, Dr Conny Helmcke, were awarded funding to work on an interdisciplinary project with the broad remit of exploring how communities in rural Scotland are making decisions about whether, why and how to restore peatlands. I thought Conny’s work on environmental justice-related themes was very cool and wanted to learn from her, so approached her to see if we could work together. A few months later, we were awarded some funds from the University of St Andrews (with thanks!) to hire a research assistant, who could collect data to explore this theme (Conny and me being ‘tied up’ with teaching). We are ever grateful to Ewan Jenkins for doing such a fantastic job of building the relationships and understanding central to the success of this project, and in the depths of a Hebridean winter.

The main output of the project, as outlined below, is a set of online (and print, on request) resources for the crofting communities that we worked with in rural Scotland. We have also published a Correspondence piece in Nature (with an open access draft here) and an article for The Conversation. And back in March of 2024, as a result of submitting evidence to a formal call, I was invited to attend the 12th Meeting of the Scottish Parliament’s Committee on Net Zero, Energy and Transport, as an invited witness to give evidence on the opportunities and impacts of natural capital finance in the Scottish context. The first set of witnesses (principally representing private landowners across Scotland) focused on the importance of private finance (and the importance of derisking private finance using public funds) for nature restoration and the achievement of net zero goals/climate change mitigation; the second set of witnesses (from Community Land Scotland, Scottish Wildlife Trust, and researchers, including me) focused on the current challenges of the focus on private finance for achieving these same goals. Here are some links to: the agenda for the session, our written evidence (Clerk Paper 1 – Annexe C), the recording of the session (starting at 10:48:00) and the Official Report. The experience was as interesting and enlightening (about the/our political process) as it was frustrating.

There are so many questions still to answer around how we can support peatland restoration whilst supporting communities, in the current climate of carbon markets, amongst other uncertainties. I hope this project doesn’t end here.

**

To give some more information on the project and resources for communities, here is an article that I wrote for the International Peatland Society’s Peatlands International quarterly communication.

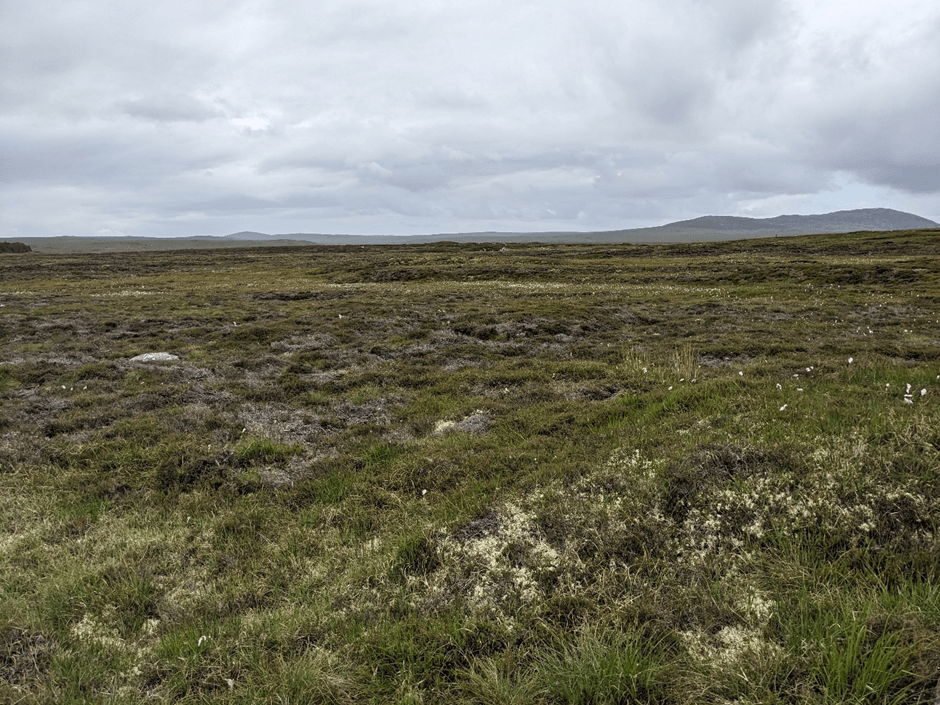

If you’re a crofter in Scotland, wanting to restore the peatland ecosystems within your communal grazing land, how do you go about it? If you have the opportunity to take advantage of public funds so that restoration costs you nothing, should you take it? Or should you agree to sell the carbon locked up in your newly restored peatland to a company or a broker, to provide you with extra revenue and them with credits to offset their emissions? What are the costs and benefits of different pathways to restoration? And how might you gain, or lose, from peatland restoration itself?

In October of 2023, colleagues and I launched an online set of resources designed to answer these questions for crofting communities living in rural Scotland, to assist them in making decisions about how to navigate peatland restoration. (Crofters are individuals who have tenure or use of a small plot of land, i.e., a croft, traditionally in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland, where commonly part of their income is obtained from farming that croft and a larger area of communal land to which they have rights to graze animals.) The website housing these resources: Peatland Restoration: A Guide for Crofting Communities, contains a downloadable Executive Summary and extended Booklet outlining some of the key considerations for crofting communities embarking on, or under pressure to engage in peatland restoration activities. Alongside these, we provide responses to common questions that arose during a period of field research carried out in the spring of 2023 in Lewis, Outer Hebrides, in the form of FAQ, as well as a glossary of terms, to facilitate understanding of the unfamiliar words and complex phrasings common in discussions around carbon credits and associated carbon markets. All of these resources (bar the FAQ) are available in English and Gáidhlig (Scots Gaelic), reflecting the languages spoken in the communities they have been designed for.

These crofter-facing guidance materials are the result of a nine-month project funded by the St Andrews Interdisciplinary Research Support scheme, awarded from the University of St Andrews, Scotland. The research underpinning the resources was carried out by a team from the University of St Andrews, led by myself and Dr Cornelia Helmcke, with Ewan Jenkins employed as a Research Fellow, and Dr Bobby Macaulay, (coordinator of the Community Landownership Academic Network (CLAN), University of the Highlands and Islands) and Drs Shona Jenkins and Milinda Banarjee (University of St Andrews), as Co-Investigators. At project inception, Cornelia and I engaged various people to understand if our research questions were pertinent and could yield information of use in the development of informed policies on peatland restoration in rural Scotland. Bobby Macaulay provided invaluable feedback on our ideas and contacts for the project, one of which was the Peatland ACTION Officer in Lewis, Ben Inglis-Grant. We thank him for the time and wisdom he shared with us over the full course of the project. Peatland ACTION is the government scheme that funds and provides logistical support for the restoration of peatlands in Scotland. Peatland ACTION is not to be confused with the Peatland Code, a UK Government-backed scheme that acts as a standard against which carbon credits resulting from peatland-based restoration projects can be verified, enabling them then to be sold on the domestic voluntary carbon market. Our project explored the challenges and opportunities associated with the different pathways to restoring peatland ecosystems within crofting communities in rural Scotland, in order to provide insights for what is necessarily a rapidly developing area of policy around natural capital markets and net zero accounting. For an important critique of the carbon market in the context of achieving net zero in the UK, pertinent to the drive for peatland carbon credits, we recommend Andy Wightman’s blog.

The website and associated resources are being disseminated to crofting communities and organisations, researchers and policy groups, and anyone who might be able to make use of the information to better understand what support and regulation is needed to help communities navigate the new potential to earn money from carbon held within, or in the case of peatlands, not emitted from landscapes if they are restored (i.e., avoided emissions if ‘Business as Usual’ scenarios continued). If you have feedback on the resources and/or would like physical copies of the Executive Summary or Booklet, please email peatlandguide@st-andrews.ac.uk.