I was invited by one of the Features editors at Business Green, “the UK’s leading source of information for the green economy” (Business Green, 2024), to write a response to a piece they’d recently published that claimed (in the title) that “The UK could lead the world on peatland carbon credits”. I accepted the challenge, in part because it would give me an opportunity to learn more about the way the peatland carbon market is currently perceived, and, provide an opportunity for me to clarify and communicate my argument as to why we need to approach this market with caution. Here’s the argument published in Business Green on 28th June 2024.

Careful investment is required to make peatland carbon credits work for the climate

An exciting economic opportunity does not necessarily equate to a feasible ecological one, writes St Andrews University’s Dr Lydia Cole

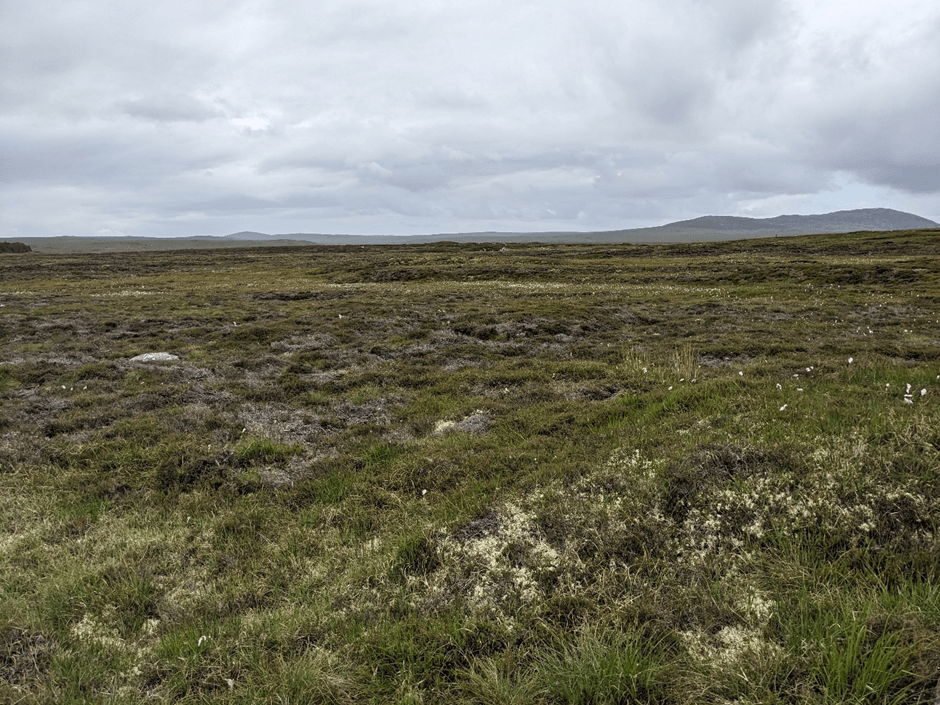

Up until recently, the UK’s peatlands – found in the murky space between terrestrial habitats and wetlands – only caught the attention of the government when land was sought for agriculture and forestry. Tax incentives in the 1970s and 1980s encouraged the drainage of these landscapes to pave the way for tree planting for timber production. But now, with international commitments under the Paris Agreement to reduce all avoidable sources of carbon emissions, our leaders are obliged to return to the UK’s damaged bogs, which are responsible for five per cent of the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions.

There is no question that blocking drains in peatlands is a necessary step towards restoring them to a healthy condition where they can again sink atmospheric carbon and contribute to mitigating global warming. There are, however, questions to answer around how we restore peatlands effectively, and how we pay for that restoration. After years of trial and error across the Northern Hemisphere, we are piecing together protocols, designing equipment and perfecting techniques for patching together peatlands, and expertise continues to grow, not least through Scotland’s publicly-funded Peatland ACTION programme.

Experience, and thus expertise, on how to fund effective peatland restoration is, however, lacking. In a recent article in BusinessGreen, the managing director of Ridge Carbon Capture Betsy Glasgow-Vasey claimed the UK could lead the world on peatland carbon credits. She may be right, but not right now. Here, I outline five areas of concern that need to be addressed if carbon credits from ‘restored’ peatlands are to contribute to our nation’s net zero goals.

Firstly, there is an assumption that the more money we invest in activities that, on paper, provide a clear pathway to climate change mitigation, the more mitigation we achieve. This is a fairassumption, but we all know how often climate-related goals are met in reality. And we all knowhow wicked and multifaceted a challenge mitigating climate change is. Take carbon credits, for example. They are supposed to lead to reduced greenhouse gases in our atmosphere. However, an UK-based individual or company can currently purchase as many carbon credits as they want via the voluntary carbon market – outside of schemes such as SBTi anyway – with no obligation to reduce their own avoidable emissions, or importantly, to have eliminated all of their avoidable emissions. If the limited stock of the UK’s carbon credits – we don’t have infinite land, let alone peatlands – is spent on such ‘greenwashing’ campaigns, we will run out of our capacity to offset the unavoidable emissions, an essential process on our pathway to achieving net zero.

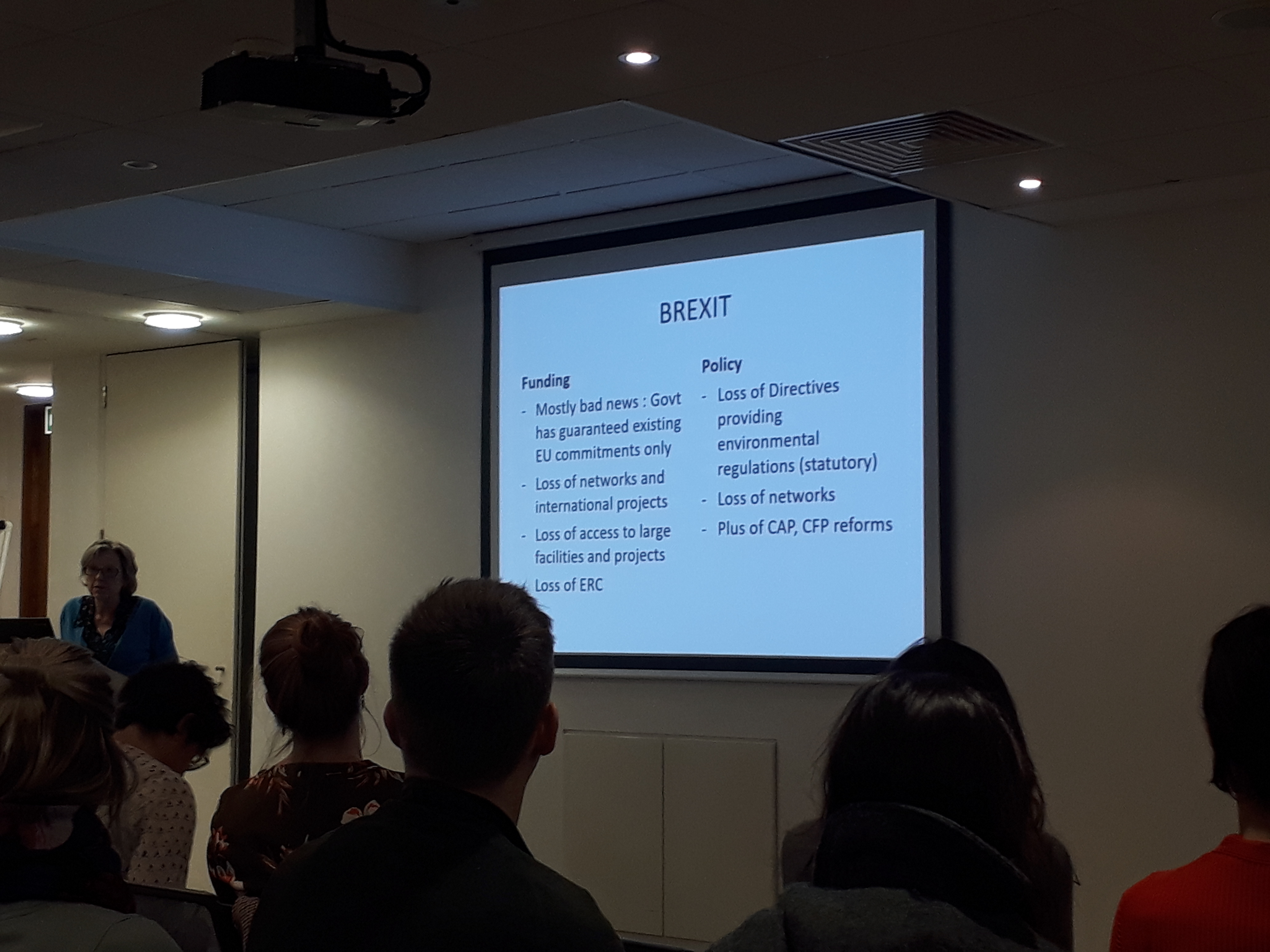

There seems to be an equally prominent assumption that the reason the UK’s peatlands are not being restored at the target rate is a lack of funding. But recent research in Scotland has suggested quite the opposite. The promise of vast payments from private investors for units of carbon that are currently sat idol is stalling the progress of publicly-funded restoration programmes. Owners and managers of peat assets are facing decision paralysis in an information vacuum: selling carbon credits could mean a reasonable revenue for the current generation, but it could also mean they forfeit access to a valuable resource and leave their inheritors with a stranded asset. The stewards of peatland carbon credits need to understand what selling those credits entails, for them now, and for future stewards. Yet they are struggling to access this information.

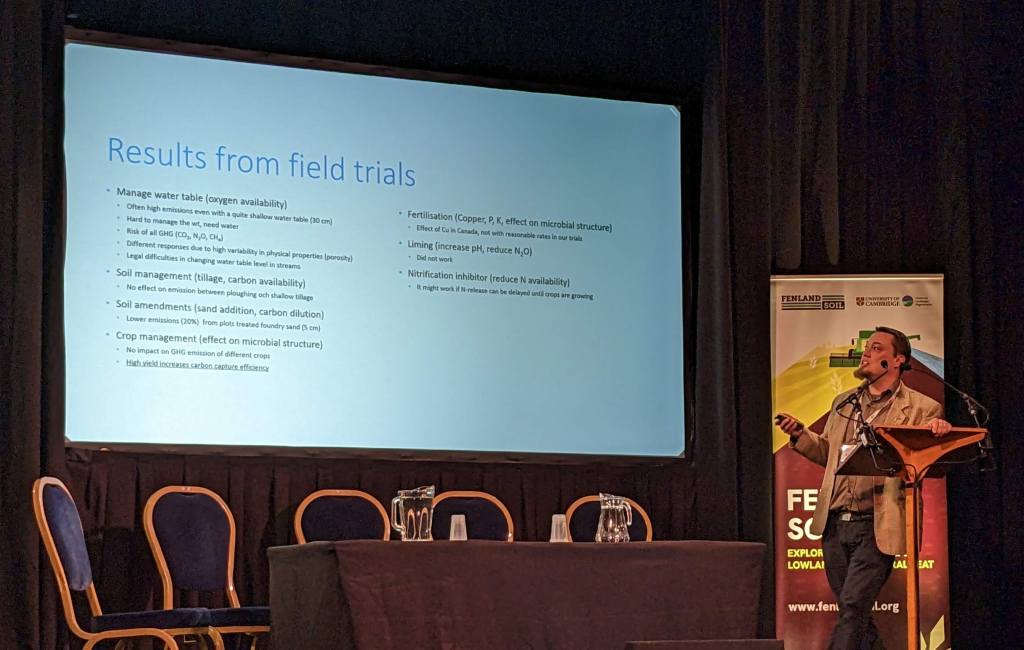

Much like there is more than one type of peatland – blanket bogs, raised bogs and fens in the UK –there is more than one type of relationship, pattern of use, land ownership regime, etc. that these stewards have with these multi-use, cultural landscapes. A carbon offsetting scheme in the intensive agricultural landscape of the Cambridgeshire Fens will necessarily look very different to one that succeeds in the crofting landscapes of the Outer Hebrides. Commodifying carbon ignores the unavoidable, and important diversity inherent in each ‘credit’, and a one-size-fits-all market, that treats all peatlands and people the same, will fail.

This market will also fail to address the problem it was created to solve – climate change – if it does not differentiate between types of carbon credits. When you block a drain in a damaged peatland, the hope is that it will start to emit less carbon as a waterlogged landscape re-establishes. This intervention will reduce the volume of carbon being emitted from the peatland initially, and lead to avoided emissions if successful, relative to the business as usual state. Overtime, if drain blocking and revegetation is successful, and climatic drying mild, that peatland might remove carbon from the atmosphere. But peatland ‘restoration’ does not necessarily equate to carbon removals or true carbon offsetting. An exciting economic opportunity does not necessarily equate to a feasible ecological one.

The Scottish Government-funded Peatland ACTION program aims to set peatlands on a “road to recovery” – to carbon sequestration in line with Scotland’s Climate Change Plan outcomes. The conditions and outcomes tied to private investments, dictated and verified via the IUCN’s Peatland Code, are necessarily prioritising market resilience above ecological. It is, of course, imperative that credit schemes entail standards that imbue confidence in investors and are paired with a healthy market through which they can flow. However, the origin of any carbon credit is a unit of carbon, and in the case of peatlands, that unit represents a real block of dark, thick, wet peat, set in a healthy ecosystem. These blocks of carbon are fragile, only replaced on millennial timescales, and will not necessarily stay put through a price tag.

A key solution to all of these notable challenges is government regulation. Carbon credits must only be available for purchase by those companies that have eliminated all of their avoidable emissions and are looking to invest – not make profit from – nature-based offsetting opportunities. And we need to be more careful with the descriptors and phrases we use to rally the crowds: “high-integrity” offsets must hold true, and “level-up the peatland industry” – what does that mean? An obligatory carbon market, similar to the UK Emission Trading Scheme (ETS), building on the ‘polluter pays’ principle, needs to have the capacity to support flexible payment models that direct funding to locally-appropriate peatland restoration or responsible management schemes. Learning from the roll-out of the Environmental Land Management Scheme (ELMS) in England, or Piloting an Outcomes Based Approach in Scotland (PoBAS) could help to build a more nuanced, more effective approach to peatland restoration that supports rural communities and leads to long-term investment in the landscapes that could make or break our collective future.

Dr Lydia Cole is lecturer at the School of Geography & Sustainable Development at University of St Andrews; chair of the Expert Group: Peatlands and Biodiversity, within the Peatlands and Environment Commission of the International Peatland Society’s Scientific Advisory Board; and Chair of Conservation Ecology Special Interest Group at the British Ecological Society.