Reposting here an article that I wrote recently for the International Peatland Society’s (IPS) Peatlands International (PI) quarterly publication. You can get access to the full publication (after becoming a member), access the back-catalogue for free, and find out who to contact if you want to write for PI here. I post this with thanks to Prof. Sue Page, for commenting on the drafted version, and to Susann Warnecke, for sending me to the FenlandSOIL gathering on behalf of the IPS, and generally for running the IPS ship so fantastically.

If you have ever enjoyed a fresh salad grown on English shores, it is likely to have comprised ingredients harvested from the Fens. A third of the country’s fresh vegetable produce comes from this region; an area of c. 3,900 km2, rich in peat. The Fens, situated across the counties of Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire, and small parts of Suffolk and Norfolk, comprise lowland agricultural peat soils, the working of which generates some £3 billion each year and employs over 80,000 people. These people and resident communities share this region with 13,000 species of plants and animals, which live within and outside of the agricultural matrix.

Another key characteristic of the Fens is that its use in food production is “an obstacle” to achieving Net Zero by 2050. Centuries of farming in this peat-rich landscape has led to vast, largely unquantified carbon emissions and to extensive wastage of the peat soil. With United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) signatory nations now required to measure, report, and reduce their greenhouse gas emissions across different sources in line with their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) to mitigating climate change, emissions from farming peat soils need to be addressed.

Cue the formation of FenlandSOIL: a cross-sectoral group tasked with exploring how farming in the Fens can be achieved in a carbon-neutral way. This farmer-led consortium was established in 2021, and now has over 80 members from the farming community, academic institutions, and multiple other public and private sector organisations.

One of the FenlandSOIL associated partnerships is that between the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and UK-based supermarket chain, Tesco. The goal of their collaboration, and of the FenlandSOIL consortium, is to answer the billion-dollar question: can we mitigate emissions whilst maintaining food production?

question of: “Can we mitigate emissions while maintaining food

production?”

On 17th and 18th April, 2023, over 200 delegates gathered to explore this question, in the small city of Ely in East Cambridgeshire, perched on an island of hard sandstone within a fenland scape. Over the two days, attendees had a chance to mix with individuals from UK Government agencies, universities (including the key collaborators from the University of Cambridge), the National Farmers Union of England and Wales, Wildlife Trusts, supermarket chains, farm equipment suppliers, and an inspiring mix of others.

females amongst the panellists!

Alongside the incoming Scientific Officer, Dr Örjan Berglund, I was fortunate to attend this fascinating, inspiring, and at times frustrating meeting of minds on behalf of the International Peatland Society. After attending the two days of presentations, observing smaller group discussions and conversing with a range of different stakeholders in the conference breaks, I identified some common themes that seemed to emerge in this cross-sectoral space. Here are some of my learnings from the event:

- No ‘one size fits all’ when it comes to developing interventions that will reduce emissions whilst enabling the food production to continue across farms in this peat-rich landscape. We need a framework to support the development of local solutions, which are bottom-up….

- …and farmer-led. Of course, there is no one size of farmer, with each having a different relationship with the landscape they are farming, but every farmer will have knowledge and experience of that multidimensional space, which must feed heavily into each stage of intervention planning and practice. The depth of knowledge, understanding and passion of farmers attending the meeting was evident. Their voices must be present and centred in policy-facing discussions.

- One skill-set farmers are often lacking is that required to carry out effective carbon management, being a relatively new role that the already hyper-skilled individuals are being tasked to take on. One farmer I spoke to was confused as to what the best approach to reducing emissions was for his farm – with his particular production system and land cover – after listening to multiple presentations advertising different emissions outcomes of different interventions for diverse production systems on different farms. An evidence-based approach is needed.

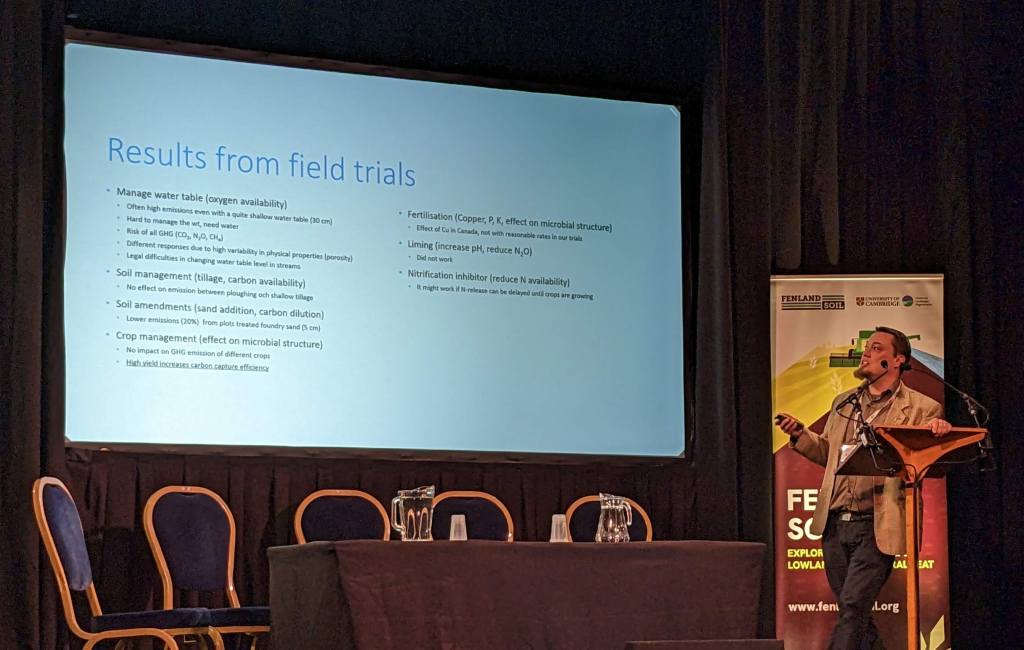

- There was a call for that evidence-base to focus on “field-scale trials and innovations”; a continuation of the no ‘one size fits all’ principle. When evidence is often place-specific, incomplete, and associated with many uncertainties, packaging it into useful guidance for farmers is one of the ultimate challenges.

- But whatever specificity of interventions are proposed, monitoring the changes in emissions, food production, soil health, species abundance, etc., and reporting those verified changes is essential, i.e., MRV – a feasible and effective Monitoring, Reporting and Verification procedure. We need to have standard, transparent, and feasible ways of assessing whether interventions are going any way to reducing GHG emissions over time, whilst not jeopardizing food production, livelihoods and other emergent properties of these systems.

- The somewhat unpredictable elephant in the room – which could undermine even the most well-designed peatland carbon management plans – is climate change. This is seen as a large risk to food production and to climate change mitigation interventions. We need to understand more about how future climatic drying and erratic weather patterns may influence peatland ecosystem health, in order that current and near-future investments in restoring wasted peats are not themselves wasted.

- The best way of climate-proofing any peatland is to manage the water table. There were plenty of discussions on storage, sharing, and managing risks associated with water across the Fens. From being a resource in abundant supply in this wetland-scape in the past, the lack of water resulting from hundreds of years of drainage is now a significant risk. Internal Drainage Boards (IDBs) are now the institutions who wield the power in these agricultural landscapes; they are in charge of decisions that can determine the economic and literal productivity of farms through water abstraction licencing. Although with transformative consequences on farming, imminent reform in licencing to reduce the exploitation of river water may create opportunities for peatland restoration. However that reform manifests, a short-term reduction in demand for water is needed across the Fens, alongside long-term local planning of water resource management, where the restoration of rivers to “good ecological status” is set as the achievable goal. As an aside, we were also reminded that water-level management in drains is not the same as water-table management in fields; each process plays a separate, yet interconnected role in peat soil conservation and food production.

- The IDBs are, of course, not acting independently but in line with national legal frameworks for water management. When it comes to policies, Government intervention, be it through legislation or financial support, is seen as a double-edged sword. Although it may not be clear how the Government could support a strategy for food production in the Fens and the variety of lowland peatlands across the UK, there were proposals for how top-level support could reduce barriers to farming in these landscapes. There were discussions relating to England’s reformulated agricultural payment schemes, e.g., the post-Brexit Environmental Land Management scheme (ELMs), and how multiples of these could be ‘stacked’ together on one farm to increase the resources available to farmers to manage these complex landscapes. Where do farmers get the equipment, the seed-stocks, and other materials and expertise (in some cases) necessary for restoring their peatlands? Could logistical barriers also be reduced through policy change?

- Or ultimately, is the lack of financial support the key challenge? Certainly, comments were made about the current lack of financial models that account for low-emissions farming practices on peatlands. We need a financial vision and framework, to accompany a logistical one.

- One of these frameworks is carbon financing, and more specifically, the Peatland Code 2.0. The IUCN UK Peatland Programme has worked to revise this standardised procedure for valuing the carbon held in peatlands under protection, with areas of the Fens now eligible for financial investment through the voluntary carbon market under this scheme.

- Regenerative agriculture is the future, we are told! I would like to believe this. But I am unsure what this is, exactly, and what it might look like in lowland peatland settings. I was reminded of the need to carefully define the terms we are using, lest they become straw men and lose their meaning, and thus power.

- Whilst sharing learning and experiences across peatland regions can be valuable, we also need to appreciate the unique nature of the Fens. Lowland peatlands behave differently to those in the uplands; the latter being the subject of the majority of financial calculations and modelling for restoration. Lowland peatlands themselves come in a wide range of shapes and sizes….

- Nuance matters. Variability in soil characteristics, water availability, and management practices across space and through time in the Fens need to be accounted for in any planning and practice. For example, the volume of Nitrous oxide emissions resulting from agriculture on peatlands may depend on the crop being cultivated and its in-field management; this detail matters.

To enable continued food production from the UK’s lowland peatlands, whilst mitigating (to some extent) carbon emissions from damaged peat soils, we need action now. We need a framework for local solutions. We need a field-scale, mosaic approach to interventions. We need to connect up communities and sectors across IDBs, and landscapes. And we need to create opportunities for social innovation. The FenlandSOIL gathering made an inspiring start.

Dr Lydia Cole

Coordinator of IPS Expert Group Peatlands and Biodiversity, University of St Andrews

lesc1@st-andrews.ac.uk