One dark evening, back in the spring of this year (2024), I agreed to join the University of St Andrew’s Student Union Debate, arguing for the motion that: This House Believes that Democracy is not the Solution to Climate Change. I don’t know when I was last a speaker in a formal debate, if I ever have been. I had little of the airs, graces, or eloquence of my opponent. And I lost. But it was fun, and I was thoroughly impressed by the confident and thoughtful responses and rebuttals of the students in the audience. Putting my argument together gave me a valuable chance to reflect on ‘democracy’ as a system of governance; something I was surprised to realise I’d not done before. I left the event feeling pretty disillusioned: the premise and promise of democracy doesn’t seem to align with what it is achieving in practice, especially in relation to the cross-national challenge of mitigating climate heating and conserving/restoring/not further massacring nature. Here’s the argument I drafted for the occasion. Further rebuttals welcome.

**

I’m speaking today, as in fact I do every day, in my capacity as an ecologist and environmental geographer, trying to understand how we, as humans, can interact with our environment in a more responsible, if not, sustainable way. I am not a political ecologist, let alone a political scientist, so my understanding of the concept and reality of democracy is relatively limited…especially outside of the UK-political context, so please bare that in mind, and forgive me if my argument and examples are not addressing the diversity of situations across the world. And I look forward to the contributions of you audience members when we open up the discussion.

Despite that disclaimer, I hope there are some points to my argument that will resonate with each of you, whatever your disciplinary background. And that some of you might side with me by the end. Although, just to mention, I did say to Alexandros [the organiser] that I could attempt to argue either for or against this motion… and as a true academic, my response when asked to provide a definitive answer is – “well, it depends”. And I look forward to agreeing, or disagreeing agreeably with the no-doubt eloquent and convincing argument that Alistair Rider [my opponent/proponent?] will put forward. Anyway, on that note, here’s is my proposition in support of “This House Believes that Democracy is not the solution to climate change”.

I’m going to start by briefly framing this topic to provide some context for the four key points of my argument.

The introduction:

Solving climate change is the most complex, wicked problem we face today. It’s important to define our terms… A wicked problem is one that involves a multidimensional challenge that – as a consequence – seems intractable, near-impossible, if not entirely impossible to solve. Hopefully This House Believes … we can solve climate change… but that’s a debate for another night! And perhaps we need to manage expectations today around how far we get to concluding this related argument.

Back to solving climate change – certainly if there is a solution, there is no ONE solution. Given a chance, different communities, in different places, will come up with different solutions for the local problems they are facing. And so if we are to have any chance of solving climate change, we/those with the power to determine people’s futures, need to be open to different perspectives – across time and space.

What is the solution to climate change?

Despite just saying that there is no one solution to climate change… actually, we all know the basic fix… Reducing emissions – reducing use of fossil fuels, supporting renewable methods of energy production, in a responsible way. And, restoring and nurturing healthy, i.e., resilient, ecosystems – as they are the absolute backbone of our physical and mental health…and fundamentally, our ability to exist on this planet. But we won’t achieve those two things without considering the justice dimension of climate change. Who is experiencing the costs of climate change? And who the benefits of resource consumption? We need to consider this both at the macro/international scale, and essentially, at the local scale – which constitutes our daily lived reality. Achieving these (aspirational) goals – reducing emissions of the gases that are warming Earth and nurturing healthy ecosystems and ensuring a fair distribution of the costs and benefits of resource consumption – requires informed, wise, compassionate governance of our local to global systems.

One way of achieving that fit-for-purpose government is through choosing them. A bit like the process of evolution by natural selection – we have a choice of parties, of varying levels of fitness, and through the way in which those different parties respond/say they’ll respond to different societal issues, such as dealing with climate change, or immigration, etc., we vote for the ‘fittest’ group. That ability for us to vote in who represents us in national decision making is the defining factor of democracy: a system of governing where those doing the decision making, who hold the power over the state/country, are acting on the instruction of the people/general population of the state.

That is how I understand it – there might be some political scientists in the room who can provide a more nuanced definition. But today, we’re not here to argue about the definition of democracy – there are bigger fish to fry! In the UK, we have the ability to vote in our leaders. Great. So, the democratic system that we have in the UK, allows us to vote in a set of compassionate, wise, rational actors, who are going to represent the whole population, and make decisions – create policies – that will ensure we all behave in a way that prioritises the long-term health of our planet. Does that resonate with any of you? Is that what’s happening? Hmm….

I’m going to argue the following four points, that illustrate how this best-case scenario is very far from the reality we’re experiencing at the moment:

- Lack of suitable leadership

- Incompatible temporal dimension of our political system

- The challenge of access to information, when it comes to voting in support of climate change policies

- The fallacy of representation in our so-called democratic systems

The argument proper:

1. Lack of suitable leadership

How many inspirational leaders do you know in government? Hands up – who can think of a politician that they would like to stand as Prime Minister? (And bear in mind you can still be a leader of a country into your 80s, we’re learning!) A ‘good’ leader is someone who actively adheres to the central principle of democracy: “state power” is actually being “vested in the people or general population of the state”. I’m going to read out a quote now – from a paper from the Institute for Local Government – “a central responsibility for public officials is to make decisions that are in the community’s interests. This is the essence of leadership in a representative democracy. Another important responsibility for public decision-makers is stewardship of the decision-making process. This involves making sure that the process is fair and that all points of view are treated with respect. Another responsibility is making sure that participants in the process have trustworthy information about the impacts—both positive and negative—about a proposal. And of course, leaders themselves need to be trustworthy. This, among other things, means telling the truth, acknowledging mistakes and being guided by what serves the community’s interests—not leaders’ personal or political interests.”

Presently, in the UK, I would argue that the party in power, that has been voted in through a democratic process, does not possess a leader with those qualities, in any of the roles which have an influence on developing policies to mitigate climate change. I look forward to anyone enlightening me on a Conservation politician I’ve under-estimated. As well as a suitable leader, or set of leaders, we need a functioning system, which won’t be independent to those leaders. We only have to look over to our neighbours in Northern Ireland to see the damage caused to society when a functioning government is absent, with no-one to make decisions. Hopefully now that Stormont, the Northern Ireland Assembly – with the decision making powers – has been re-established after about seven years of a governance vacuum (2017), leaders can start to repair public services and look towards the environment.

2. The time dimension of our political system and its incompatibility with making decisions about long-term change

During a political party’s time in office, they’re looking to make people as happy as possible, as quickly as possible, so that those people [the ‘general public’] vote for the same party again, at the end of that party’s term. Feelings of happiness, or atleast satisfaction amongst the voting public, often result from improved standards of living – more housing, cheaper travel to sunny places, lower council tax…and other factors that are almost entirely incompatible (at first sight, anyway) with investing in longer-term changes that will reduce emissions and nurture the environment. For example, air travel – how are we going to reduce emissions if flights are becoming cheaper? How are we going to protect green spaces if we expand our airports? How are we going to improve train travel – both accessibility of ticket prices and the condition of the infrastructure and reliability of the service – if public funds are spent on subsidising aviation fuel?

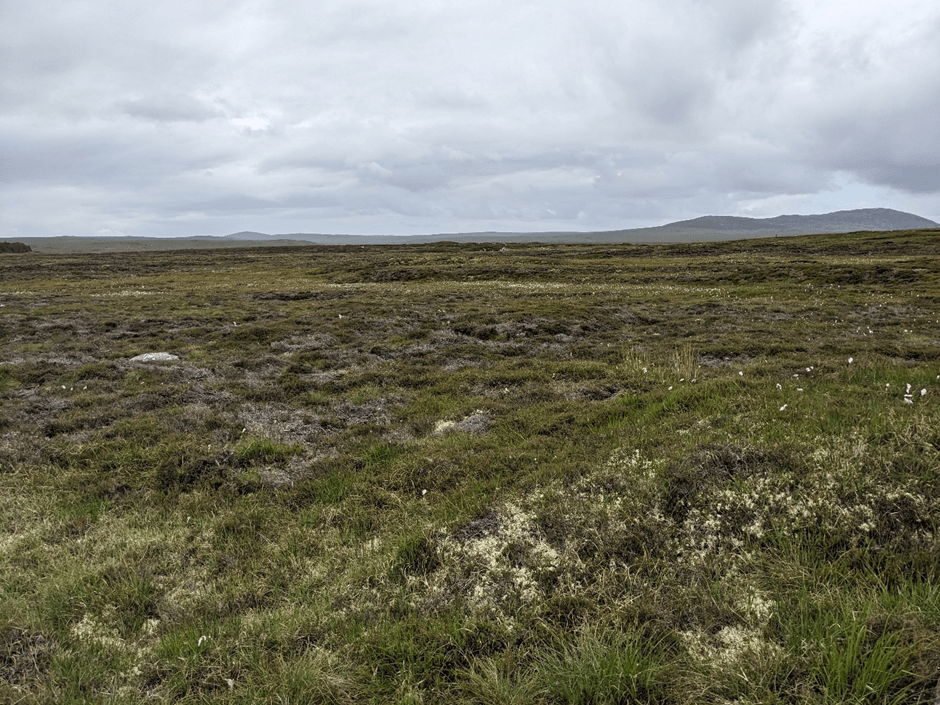

Restoring ecosystems back to health, such as peatlands, which are my pet and professional passion, requires a commitment to financial and infrastructural support over what would be up to 20 electoral cycles – 100 years. But most Governments aren’t thinking along those lines. And try to avoid diverting precious resources that could be directed towards efforts to keep them in power for longer…so that they can be powerful for longer… or whatever their manifesto states their goals are whilst in government?! We need longer-term thinking – in tune with ecological dynamics – to be incorporated much more into policy making. Perhaps on this point, a benevolent dictatorship might lead to more sustained action over time? Perhaps someone can argue for/against that statement later.

3. Prioritisation – Information availability to guide voting

My next point is around what informs our vote. I’ve been noting increasing calls from respected public figures, such as the primatologist and climate change/humanitarian activist, Jane Goodall, telling us to vote wisely in our next elections, to vote in people and political parties who will actually address (as far as we can currently tell via publicly available manifestos pledges) climate change. Reminded of this quote by the American author/critique of the early 20th century – George Jean Nathan – “Bad officials are elected by good citizens who do not vote.” Us voting “wisely” relies on a “general population of a state” having sensible, community-/climate-minded priorities.

But do we vote wisely? (Rhetorical!) How do we know what ‘wisely’ constitutes when we’re bombarded with information from different dubious media masquerading as evidence-based sources? The press, shaping our echo chambers, probably has a lot to answer for when it comes to the voting public making unwise decisions on which political party would best serve them when in power. And what happens if a matter of public interest is “too complex” for the lay person to understand? And no-one is making that information adequately accessible? Then there’s even more likelihood that people won’t make decisions in their best interest, and be swayed by information that is presented to them in an accessible way. If people are provided with more information that is useful to them and influences their lived experience and identity, they are more likely to act on it, and prioritise changes that might be beneficial for them, their family and their local community. And if people are more involved in the process of generating new knowledge – so in research, the life-blood of institutions such as our own – they will feel more empowered to act on it, feel there is hope and opportunity to change, and likely be more outward-looking. If they’re not involved in important societal processes, and don’t feel they are being served by the state or institutions in it, they will start to distrust, disrespect, disconnect from these processes, and become more concerned with their own affairs – focus in on their own back garden.

Fundamentally, if people cannot satisfy their basic needs – feel included, feel valued and respected, feel part of a community, and have hope for the future – they are very unlikely to look beyond their needs. They might not even have the capacity to care for their back garden, let alone the health of their local park – or the CO2 emissions they are responsible for, or the wildlife living in their neighbourhood. We need to support people to get to a point where their needs are met such that they have the capacity to care about climate change and consider how best to act to mitigate it.

4. Representation of the “whole population”

Is the process of voting equitable? Is everyone invited and able to vote on matters that will affect their future? Certainly, I’ve heard stories from the US recently about the challenges that some more marginalized communities face in trying to physically get to voting stations. This lack of accessibility – unintended or intended – means that not all of the population is being represented. Also, children – people under the age of 18 – are not invited to vote in the UK. We could argue whether this is a good or bad thing… But what if we allowed students who were engaged in Fridays for Future to vote? What if all of those children inspired by the great Greta Thunberg were able to vote in a way that might give them some hope for their future? Some medicine for their entirely justified climate anxiety? Or the young adults engaged in programmes such as those run by the charity – Action for Conservation, which takes secondary school students from deprived backgrounds out into nature, to experience it and be inspired to build a sense of care towards it. Those individuals are not currently being represented in our democratic system. Yet they are the ones who will be in charge of organizing the future mess that the system is creating at present.

And is the ‘population’, as we’re defining it, an appropriate unit? The people of Scotland act as a population, able to vote to shape decisions that will affect them related to health care, education, transport… via the devolved Government based in Holyrood. But they have a much more diluted voice when they vote in elections, referenda, which are administered by the UK/Westminster government, e.g., whether to leave the EU or not. Democracy leads to different outcomes at different geographical/political scales. Perhaps I would be arguing against the motion if we had many more devolved democratic populations across the UK/world.

This is a particular topic of interest in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland right now – where I’ve been doing some research – as many communities would like much more ability to influence decisions that really impact on their lives, such as what sorts of rural ‘development’ they want to engage in – rather than have those decisions made by extra-local parties who aren’t aware of their local experience / lived reality in those spaces. Perhaps Community Land Trusts should be given the chance to shape their own climate change mitigation strategies, for example, rather than Holyrood defining these, or even more unhelpfully, Westminster. If democracy is to prove the solution, we need to divide up our democratic units in a sensible way, grouping communities of interest who care, and have the capacity – resources and relationships – to take responsibility for the long-term health of their communities and environment.

Some concluding remarks then…

As I mentioned at the start, there is NO ONE solution to climate change. So definitely, I believe that Democracy is not the solution. In terms of the democracy element… capital D-Democracy is a system of politics that should distribute power to the people … but it only does that, if it actually does do that – distribute power to the people through creating environments in which everyone can play a role in decision making that will affect their lives. And create environments where people – the voting public – have access to information that will help them to understand the impact different decisions might have on them and future generations. There are many, including currently in the UK, examples of where democratic decision making is not occurring – decisions impacting on the many are being made by the few, or certainly not through consensus. And those few people making the decisions – whether perceived to be democratically elected or not – are not acting in a way that prioritises solving the climate challenge. I will end my speech with a call for systems of governance that center communities, and collaborative, creative and compassionate approaches to solve the coupled climate and nature conundrum.