Reposted from the BES Conservation Ecology SIG website.

At my last meeting as Chair of the Conservation Ecology Special Interest Group (SIG), I shared a few thoughts, and a few thanks, with my wonderful committee. Afterwards, they asked me to pop them down on (virtual) paper. So, here they are.

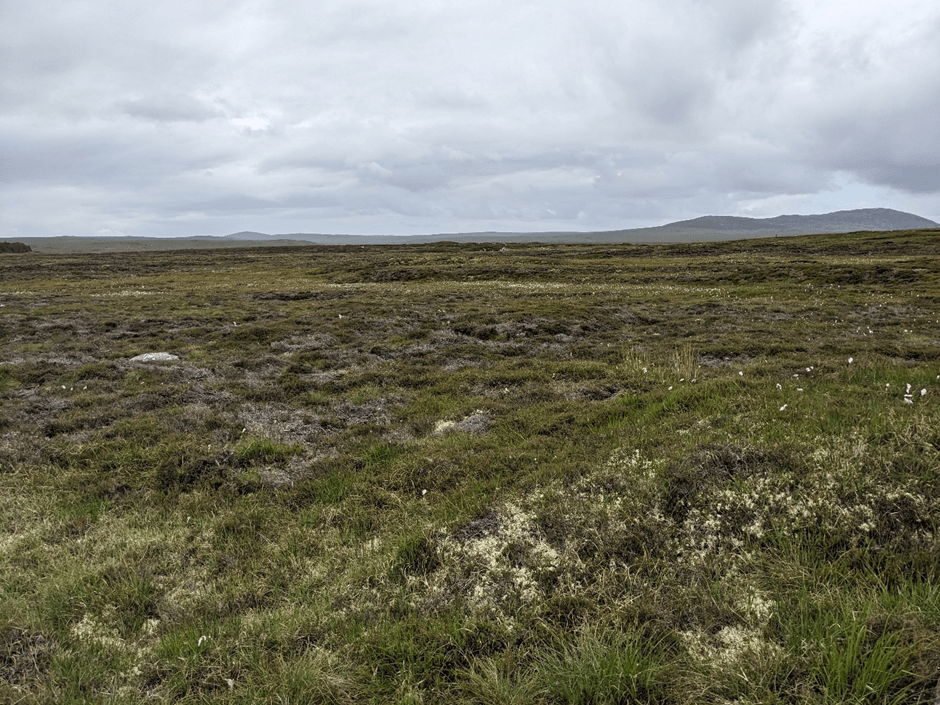

Back in 2015, I was looking for opportunities to become more connected with the activities of the British Ecological Society (BES), having completed my PhD in 2013 and moved into ‘industry’. I was fearful of moving too far from my ecological routes, and from research, as I sought employment where there was some! I was very fortunate to stumble into a job as an Environmental Scientist at a then budding big data company, where I would spend weeks on end trudging across my favourite ecosystem, peatlands.

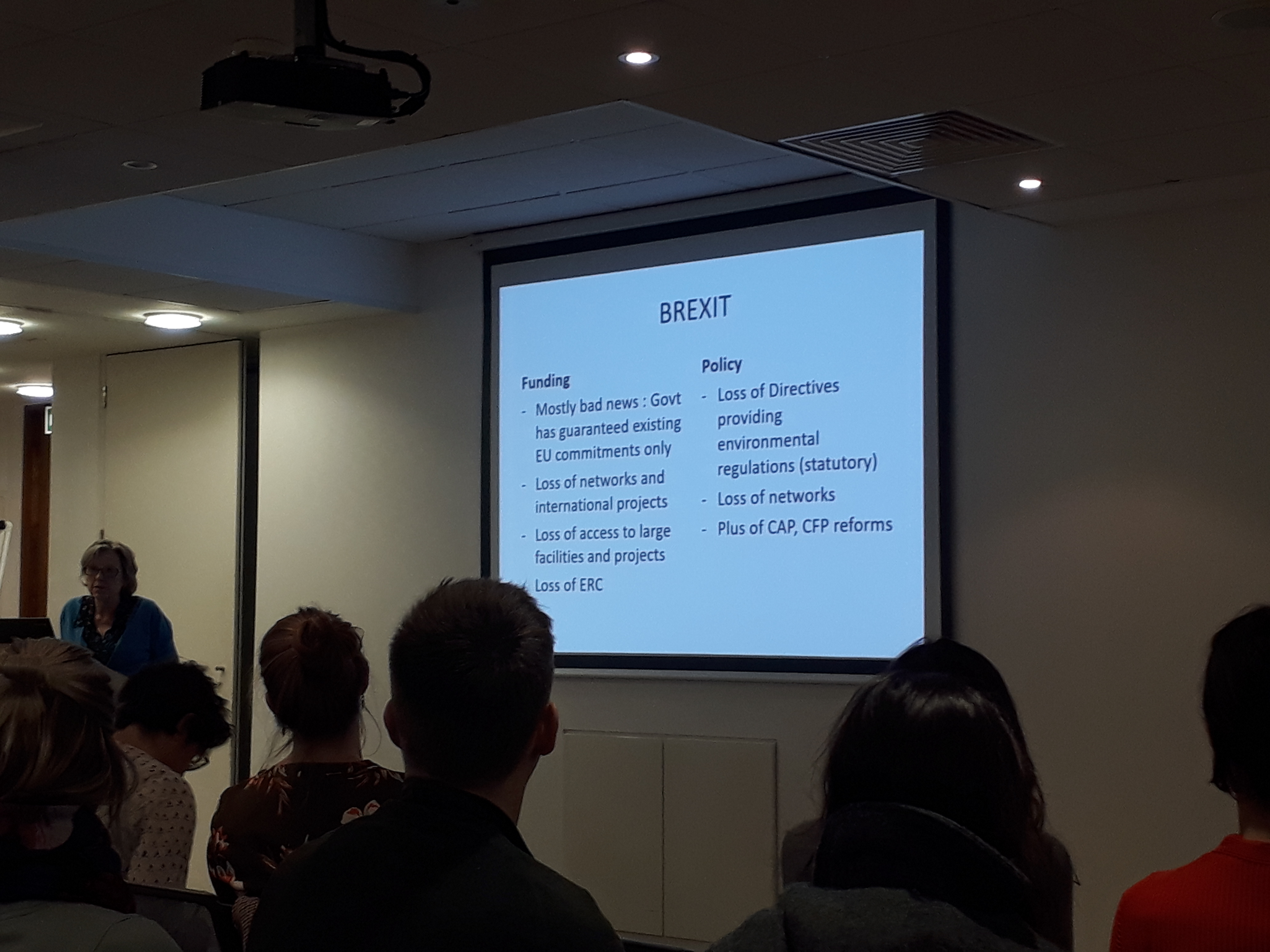

Joining the Conservation Ecology Committee at that point in time provided all sorts of opportunities, from informal mentorship from the Chair of the Special Interest Group (SIG) at the time, the fabulous Prof. Natalie Pettorelli, to getting experience in co-organising well-attended career and policy-focused events, to exposure to great minds (including the wonderful Georgina Mace), and to new friends (committee members who have ‘served’ as long as me), and to being a part of a supportive, hopeful and vibrant community of ecologically-minded folks.

In 2018, Natalie stepped down from the Committee, leaving a big hole. I’d not realised at the time that I was second-in-command, and was asked by the BES to plug the hole. I was very reluctant to: I didn’t feel I had the time, experience, or confidence to take on the role. But, apparently, I did. And eight years later, I’m passing the (far from poisoned) chalice on to someone else.

The usual term for a Chair is three years, and, in fact, it’s healthy to change the leader regularly, to bring in new ideas, give someone else a chance at a leadership role, ensure the incumbent chair doesn’t get too power-hungry, etc. I suggested the Committee launch a coup to oust me multiple times, but that proposal was never taken up by anyone…so I kept calm and carried on.

Aside from the distinct lack of a coup, or of someone keen to step up into the role, I was also in no rush to step down. Being a chair of a BES SIG is a real privilege. There is work involved, as with everything in life, and it does consume time that could otherwise have been spent on the hamster-wheel activities of my meandering career path… but, there is also great reward. I’ve spent eight+ years getting to know and work with a passionate and skilled bunch of early career ecologists and ecology-aligned researchers and practitioners, each of whom has filled/is filling their particular niche on our SIG committee. It’s also been a pleasure, and a rewarding experience (in all sorts of ways), to be an official part of the BES community. The BES does feel like a community, and always has for me. This British institution is full of equally passionate and skilled individuals, working to enthuse people in the science, practice and lived experience of ecology, with the goal of making the innumerable and indescribable benefits of the natural world available to us all, forever. A big challenge, but a fun one.

At my final Conservation Ecology committee meeting as Chair, I thought I would share some of the things I’ve learnt over the years; impart some advice, perhaps. First, wear sunscreen, of course. Aside from that, I encouraged all of the team to make the most of the opportunity of being on the committee – with the committee being a safe place to develop their own personal style of leadership, to build skills through activities they know they enjoy doing (e.g., writing blogs) and to trial new skillsets that they might enjoy (e.g., becoming a podcast host). Connecting more with the BES and networks within it, was also a key piece of advice; you’re tapping into a huge ecosystem of brilliant people when you join a SIG, especially in a committee role. And, fundamentally, each member of the SIG has a chance to contribute to a safe, nurturing environment where individuals can build confidence, skills, and opportunities for themselves and others in our community, towards a more positive future. I know no person is an island and all that, but I also believe change starts at home, and that home is, in fact, the only place where change ever starts. We have more agency than we often realise. Which is what Project Forward is all about: creating opportunities for people to develop the skills and confidence to shape a more just and healthy future.

I am fortunate to report that the Conservation Ecology SIG is under fantastic new management; I have every confidence in Dr Jessica William’s leadership skills and am excited to see what direction she takes the community in. I’ve been blessed with a fabulous SIG committee over the last eight years, through multiple iterations, complete with a great bunch of stalwarts (now our Extra-Ordinary Members – you know who you are). Thanks to all of them for eight years of inspiration and fun. And, ofcourse, thanks be to the goats.

Over and out. Lydia Cole. Conservation Ecology SIG Chair 2018-2026.